Joseph Stalin (Russian: Иосиф Виссарио́нович Сталин, Iosif Stalin Georgian: იოსებ სტალინი), born as Iosef Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili[note 1] December 18 [O.S. December 6] 1878 – March 5, 1953) was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee from 1922 until his death in 1953.[note 2][1][2] During that time he established the regime now known as Stalinism. He gradually consolidated power and became the de facto party leader and dictator of the Soviet Union.[3]

Following the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, Stalin prevailed in a power struggle over Leon Trotsky, who was expelled from the Communist Party and deported from the Soviet Union. Stalin launched a command economy in the Soviet Union replacing the New Economic Policy of the 1920s with Five-Year Plans in 1928 and at roughly the same time, forced rapid industrialization of the largely rural country and collective farming by confiscating the lands of farmers. He derogatorily referred to farmers who refused his reforms as "kulaks", a class of rich peasant which had in actual fact been wiped out by World War One; millions were killed, exiled to Siberia, or died of starvation after their land, homes, meager possessions, and ability to earn an existence from the land were taken to fulfill Stalin's vision of massive "factory farms"[4]. While the Soviet Union transformed from an agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse in a short span of time, millions of people died from hardships and famine that occurred as a result of the severe economic upheaval and party policies.[5][6][7]

At the end of 1930s, Stalin launched the Great Purge, a major campaign of political repression. During his continued repressions, millions of people who were a threat to the Soviet politics or suspected of being such a threat were executed or exiled to Gulag labor camps in remote areas of Siberia or Central Asia, where many more died of disease, malnutrition and exposure. A number of ethnic groups in Russia were forcibly resettled for political reasons. Stalin's rule, reinforced by a cult of personality, fought real and alleged opponents mainly through the security apparatus, such as the NKVD. In the 1950s Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's eventual successor, denounced Stalin's rule and the cult of personality, thus initiating the process of "de-Stalinization".

Bearing the brunt of the Nazis' attacks, the Soviet Union under Stalin made the largest and most decisive contribution to the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II (1939–1945). Some historians believe Stalin contributed to starting World War II because of his secret agreement with Nazi Germany to carve up the nation of Poland, as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. This led to the Soviet Union's invasion of Poland from the east later that same year, following Nazi Germany's invasion of western Poland. Under Stalin's leadership after the war, the Soviet Union went on to achieve recognition as one of just two superpowers in the world. That status lasted for nearly four decades after his death until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Stalin's rule had long-lasting effects on the features that characterized the Soviet state from the era of his rule to its collapse in 1991.

| Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin იოსებ ბესრიონის სტალინი Иосиф Виссарионович Сталин | |

| |

|

| |

|---|---|

| In office April 3, 1922 – March 5, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | None (position created in 1922) |

| Succeeded by | Nikita Khrushchev |

|

| |

| In office May 6, 1941 – March 5, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov |

|

| |

| Born | December 18, 1878(1878-12-18)[1] Gori, Georgia, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 5, 1953 (aged 74) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Religion | None (atheist) |

Childhood and education, 1878–1899

|

|

| Official portrait of Stalin's father, Vissarion | Stalin's mother, Ekaterina |

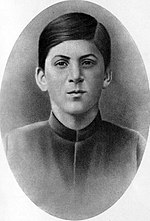

Joseph Stalin was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in Gori, Georgia to Vissarion Dzhugashvili and Ekaterina Geladze. Stalin's mother was born a serf. His father was a cobbler and owned his own workshop. He was their third child; their two previous sons died in infancy. The second and third toes of his left foot were webbed.[8]

Initially, the Dzhugashvilis' lives were prosperous and happy, but Stalin's father became an alcoholic,[9] which gradually led to his business failing and his becoming violently abusive to his wife and child. As their financial situation grew worse, Stalin's family moved homes frequently; at least nine times in Stalin's first ten years of life.[10]

The town where Stalin grew up was a violent and lawless place. It had only a small police force and a culture of violence that included gang-warfare, organized street brawls and wrestling tournaments (some of these were traditions inherited from Georgia's war-torn past).[10] Stalin took part in streetfighting as a child; he was not afraid to challenge opponents who were much stronger than he, and he was severely beaten on numerous occasions.[10]

At the age of 7, Stalin fell ill with smallpox and his face was badly scarred by the disease. He later had photographs retouched to make his pockmarks less apparent. Stalin's native tongue was Georgian. He started learning Russian only when he was eight or nine years old, and he never lost his strong Georgian accent.

At the age of 10, Stalin began his education at the Gori Church School. His peers were mostly the sons of affluent priests, officials, and merchants. He and most of his classmates at Gori were Georgians and spoke mostly Georgian. However, at school they were forced to speak Russian (this was the policy of Tsar Alexander III). Their Russian teachers mocked the accents of their Georgian students, and regarded their language and culture as inferior. Nevertheless, Stalin earned the respect and admiration of his teachers by being the best student in the class, earning top marks across the board. He developed a passion for learning that stayed with him for the rest of his life. He became a very good choir singer and was often hired to sing at weddings. He also began to write poetry, something he would develop in later years.[10]

Stalin's father, who had always wanted his son to be trained as a cobbler rather than be educated, was infuriated when the boy was accepted into the school. In his anger he smashed the windows of the local tavern, and later attacked the town police chief. Out of compassion for Stalin's mother, the police chief did not arrest Vissarion, but ordered him to leave town. He moved to Tiflis where he found work in a shoe factory and left his family behind in Gori.[10]

About the time Stalin began school, he was struck by a horse-drawn carriage. The accident permanently damaged his left arm; this injury would later exempt him from military service in World War I. At the age of 12, Stalin was struck again by a horse-drawn carriage and injured badly. He was taken to hospital in Tiflis where he spent months in care. After he recovered, his father seized the opportunity to kidnap the boy and enroll him as an apprentice cobbler at the shoe factory where he worked. When his mother, through the aid of contacts in the clergy and school staff, recovered the boy, his father cut off all financial support to his wife and son, leaving them to fend for themselves. Stalin returned to his school in Gori where he continued to excel.[10]

He graduated first in his class and in 1894, at the age of 16, he enrolled at the Georgian Orthodox Seminary of Tiflis, to which he had been awarded a scholarship. The teachers at Tiflis Seminary were also determined to impose Russian language and culture on the Georgian students.[10] Like many of his comrades, young Stalin reacted by being drawn to Georgian patriotism. During this time he gained fame as a poet; his poems were published in several local newspapers. However, his interest for poetry began to fade as he was drawn to rebellion and revolution.

During his time at the seminary, Stalin and numerous other students read forbidden literature that included Victor Hugo novels and revolutionary (including Marxist) literature. He was caught and punished numerous times for this. One teacher in particular - Father Abashidze, whom Stalin nicknamed "the Black Spot" - harassed the rebel students through student informers, nightly patrols and surprise dormitory raids. This personal experience of "surveillance, spying, invasion of inner life, violation of feelings", in Stalin's own words, influenced the design of his future terror state.[10] He became an atheist in his first year.[10] He insisted his peers call him "Koba", after the Robin Hood-like protagonist of the novel The Patricide by Alexander Kazbegi; he would continue to use this pseudonym as a revolutionary. In August 1898, he joined the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (from which the Bolsheviks would later form).

Shortly before the final exams, the Seminary abruptly raised school fees. Unable to pay, Stalin quit the seminary in 1899 and missed his exams, for which he was officially expelled.[10] Twenty of his fellow-classmates were expelled for revolutionary activities in 1899, and forty more were expelled in 1901.[11] Shortly after leaving school, Stalin discovered the writings of Vladimir Lenin and decided to become a revolutionary.

Early years as a Marxist revolutionary, 1899–1917

After abandoning his priestly education, Stalin took a job as a weatherman at the Tiflis Meteorological Observatory. Although the pay was relatively low (20 roubles a month), his workload was light, giving him plenty of time for revolutionary activities. He would organise strikes, lead demonstrations and give speeches. He soon caught the attention of the Tsar's secret police, the Okhrana. During this time he met and charmed Simon Ter-Petrossian, a violent psychopath who became his long-time henchman and enforcer.[12]

On the night of April 3 1901 the Okhrana arrested a number of SD Party leaders in Tiflis, but Stalin spotted their agents waiting in ambush at the Observatory and avoided capture. He went underground, becoming a full-time revolutionary, living off donations from friends, sympathizers and his Party. He began writing revolutionary articles for the Baku-based radical newspaper Brdzola ("Struggle").[10]

In October, Stalin fled to Batumi and got work at an oil refinery owned by the Rothschild family. Organizing the workers there, Stalin was almost certainly involved in a 1902 fire at the refinery designed to trick the management into giving the workers a bonus for putting out the fire. However, the manager suspected arson and refused to pay. This led to a series of strikes, all organized by Stalin, which in turn led to arrests and clashes with the Cossacks in the streets. In one attempt to break their comrades out of prison, thirteen strikers were killed when Cossacks intervened. Stalin distributed incendiary pamphlets portraying the dead as martyrs. On April 18 1902, the authorities finally arrested Stalin at one of his secret meetings. At his trial, Stalin was acquitted of leading the riots due to lack of evidence, but was kept in custody whilst the authorities investigated his activities in Tiflis. In 1903, the authorities decided to exile Stalin to Siberia for three years.[10]

Stalin ended up in the Siberian town of Novaya Uda on December 9 1903. During this time, he heard that two rival factions within the Social-Democrats had formed: the Bolsheviks under Lenin and the Mensheviks under Julius Martov. Stalin, already an admirer, decided to become a Leninist. Stalin managed to obtain false papers and, on January 17 1904, escaped Siberia by train, arriving back in Tiflis ten days later.[10]

With no income, Stalin lived off his circle of friends. One of them introduced him to Lev Kamenev (then known as Lev Rosenfeld), his future co-ruler of the USSR after Lenin's death. At this time, Stalin favored a Georgian Social-Democratic party, which caused a rift with the majority who favored international Marxism. Threatened with expulsion, he was forced to write Credo, a paper renouncing his views (because this paper distanced himself from Lenin, when Stalin became ruler of the USSR, he tried to destroy all copies of this Credo, and many of those who had read it were shot).[10]

In February 1904, the Russo-Japanese War broke out between Japan and Russia. The war, which would eventually end in Russia's defeat, severely strained the Russian economy and caused a great deal of restlessness in Georgia. Stalin travelled across Georgia conducting political activity for his party. He also worked to undermine the Mensheviks through a campaign of slander and intrigue; his efforts brought him to Lenin's attention for the first time.

On January 22 1905, Stalin was in Baku when Cossacks attacked a mass demonstration of workers, killing two hundred. This sparked off the Russian Revolution of 1905. Riots, peasant uprisings and ethnic massacres swept the Russian Empire. In February, ethnic Azeris and Armenians were slaughtering each other in the streets of Baku. Commanding a squad of armed Bolsheviks, Stalin ran protection rackets to raise Party funds and stole printing equipment. Afterwards, he headed west, where continued to campaign against the Mensheviks, who enjoyed overwhelming support in Georgia. In the mining town of Chiatura, both Stalin and the Mensheviks competed for the support of the miners; they chose Stalin, being more swayed by his plain and concise manner of speaking than the flamboyant oratory of the Menshevik speaker.[10] From Chiatura, Stalin organized and armed Bolshevik militias across Georgia. With them, he ran protection rackets among the wealthy and waged guerilla warfare on Cossacks, policemen and the Okhrana.[10] Later that year in Tiflis, he met Ekaterina Svanidze, who would become his first wife.

In December 1905, Stalin and two other were elected to represent the Caucusus at the next Bolshevik conference, which took place in Tammerfors, Finland. There, on January 7 1906, Stalin met Lenin in person for the first time. Although Stalin was impressed by Lenin's personality and intellect, he was not afraid to contradict him.[10] He objected to Lenin's proposal that they take part in elections to the recently-formed Duma; Lenin conceded to Stalin. At the conference he also met Emelian Yaroslavsky, his future propaganda chief, and Solomon Lozovsky, his future Deputy Foreign Commissar.

After the conference, Stalin returned to Georgia, where Cossack armies were brutally working to reconquer the rebellious region for the Tsar. In Tiflis, Stalin and the Mensheviks plotted the assassination of General Fyodo Griiazanov, which was carried out on March 1 1906. Stalin continued to raise money for the Bolsheviks through extortion, bank robberies and hold-ups.

In April 1906, Stalin attended the Fourth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. At the conference, he met Klimenti Voroshilov, his future Defence Commissar and First Marshal; Felix Dzerzhinsky, future founder of the Cheka; and Grigory Zinoviev, with whom he would share power after Lenin's death. The Congress - in which the Bolsheviks were outnumbered - voted to ban bank robberies. This upset Lenin, who needed the bank robberies to raise money.[10]

Stalin married Ekaterina Svanidze on the night of July 28 1906. On March 31 1907, she gave birth to Stalin's first child, Yakov.

Stalin and Lenin both attended the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in London in 1907.[13] This Congress consolidated the supremacy of Lenin's Bolshevik faction and debated strategy for communist revolution in Russia. Here, Stalin first met Leon Trotsky in person; Stalin immediately came to hate him, calling him "pretty but useless".[10] After the conference, Stalin began switching his focus away from Georgia, which was rife with feuding and dominated by the Mensheviks, to Russia; he began writing in Russian.

Upon his return to Tiflis, Stalin readied himself for a major bank robbery. Through contacts in the banking business, he had learned a major shipment of money was due to be delivered in June to the Imperial Bank at the centre of town. Because his party banned bank robberies, Stalin temporarily resigned. On June 26 1907, Stalin's gang ambushed the armed convoy when it entered Yerevan Square with gunfire and homemade bombs. Around forty people were killed, but all of Stalin's gang managed to escape alive with 250,000 roubles (around US$3.4 million in today's terms).[10] Stalin and his family left Tiflis two days later. His henchman Kamo delivered the money to Lenin in Finland, who then fled with it to Geneva. The Mensheviks, who had banned bank robberies (and didn't get to share in the loot), were outraged and investigated the suspects. Stalin escaped expulsion, though the affair would cause him trouble for years to come.

Stalin's family moved to Baku. Whilst Stalin continued his revolutionary activities, his wife fell ill from Baku's pollution, heat, stress and malnourishment. She eventually contracted typhus (though many historians believe it to have been tuberculosis) and died on December 5 1907. Stalin was overcome with grief and retreated into mourning for several months. The loss also hardened him; he told a friend: "with her died my last warm feelings for humanity".[10] He abandoned his son, Yakov, who was raised by his deceased wife's family.

When Stalin resumed his activities, he organized more strikes and agitation, this time focusing on the Muslim Azeri and Persian workers in Baku. He helped found a Muslim Bolshevik group called Himmat, and also supported Persian Constitutional Revolution with manpower and weapons, and even visited Persia to organize partisans. Stalin ordered the murders of many Black Hundreds (right-wing supporters of the Tsar), and conducted protection rackets and ransom kidnappings against the oil tycoons of Baku . He also operated counterfeiting operations, robberies and protection rackets. He befriend the criminal gangs, and used them to obstruct Mensheviks. Stalin's gangsterism upset the Bolshevik intelligentsia, but he was too influential and indsipensable to oppose.[10]

The Okhrana tracked down and arrested Stalin on April 7 1908. After seven months in prison, he was sentenced to two years exile in Siberia. He arrived in the village of Solvychegodsk in early March 1909. After seven months in exile, he disguised himself as a woman and escaped on a train to St Petersburg. He returned to Baku in late July.[10]

The Bolsheviks were on the verge of collapse due to Okhrana oppression within the Empire and infighting among the intelligentsia abroad. In desperation, he advocated a reconciliation with the Mensheviks (which Lenin opposed). He demanded the creation of a Russian Bureau to run the Social-Democratic Party from within the Empire, to which he was appointed.

Stalin soon realised the Bolsheviks had been heavily infiltrated by Tsarist spies. He initiated a witch-hunt for traitors, however, he failed to root out any real traitors - as revealed by Okhrana records - and his efforts caused much disarray in the Party.[10]

On April 5 1910 Stalin was yet again arrested by the Okhrana. He was banned from the Caucasus for five years and sentenced to complete his previous exile in Solvychegodsk. He was deported back there in September. He briefly escaped in early 1911, but another exile who was supposed to pass much-needed money to him instead ran off with it (Stalin would have him shot for this in 1937), and he was forced to return to Solvychegodsk. During his exile, he fell in love with a local girl, Maria Kuzakova, with whom he fathered a child. He was released on July 9 1911. Stalin moved to Vologda in late July, where he had been ordered to reside for two months.

In January 1912, at the Prague Party Conference, Lenin led his Bolshevik faction out of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, founding the separate Bolshevik Party. Stalin was coopted as a member of the new Bolshevik Central Committee. When Stalin was informed of this, he left Vologda in late February.

Stalin moved to Saint Petersburg in April 1912, where he took control of the Bolshevik weekly newspaper Zvezda. Stalin had been assigned to convert Zvezda into a daily and rename it Pravda. The first issue was published on May 5.

Shortly afterwards, the Okhrana caught up with him again, and in July 1912 he was exiled again to Siberia for three years, this time in the small village of Narym. He escaped just thirty-eight days after arriving; this was his shortest exile.[10] He returned to Saint Petersburg in September.

Stalin made efforts to reconcile the Bolsheviks with the Mensheviks in hopes of salvaging the struggling Marxist movement. He published editorials in Pravda advocating reconciliation, and secretly met with Menshevik leaders on several occasions. This angered Lenin, who twice summoned Stalin to Kraków to argue policy. On the second visit at the end of 1912, Stalin was removed from his post as editor of Pravda, but was made a leader of the Russian Bureau of the Bolshevik Party. Lenin also asked Stalin to write an essay laying out the Bolshevik position on national minorities.

After Kraków, Stalin spent several weeks in Vienna with the Troyanovskys, a wealthy Bolshevik couple he met with Lenin in Kraków. Whilst there he met for the first time Nikolai Bukharin, who would become a leading politician in the future Soviet government. They continued to discuss the issue of nationalities. Stalin completed his essay on the topic, entitled "Marxism and the National Question", which was published in March 1913 under the pseudonym "K. Stalin" (this was the first time he used the name "Stalin" in a publishing; he began using this alias in 1912).

Stalin returned to Saint Petersburg in February 1913. During this time, many Bolsheviks, including almost the entire Central Committee, had been arrested by the Okhrana, having been betrayed by Roman Malinovsky, a high-ranking Bolshevik who for years had been an Okhrana spy and agent provocateur. That month, an article had been published that outed Malinovsky as a spy, but the Bolsheviks dismissed it as Menshevik libel (ironically, Lenin and Stalin were his strongest defenders). On March 8 Malinovsky persuaded Stalin to attend a Bolshevik fundraising ball, which was raided by the Okhrana.

Stalin was condemned to four years in the remote Siberian province of Turukhansk. He was eventually joined by Kamenev and several other Bolshevik exiles. He spent six months in the small hamlet of Kostino on the Yenisei River. After learning that Stalin was planning an escape (he had received money and supplies from his comrades), the authorities moved him north to Kureika, a hamlet on the edge of the Arctic Circle. There, he lived the life of a hunter-gatherer, having learned fishing and hunting from the local Siberian tribesmen. While there he began a 2-year affair with Lidia Pereprygina, then aged 13, with whom he fathered two children. The first died in infancy; the second, named Alexander, was born in April 1917.

In late 1916, Stalin was conscripted into the army. He was taken Krasnoyarsk in February 1917, but the medical examiner there found him unfit for service due to his damaged left arm (a childhood injury). He spent his last four months of exile in the village of Achinsk.

Russian Revolution of 1917

In the wake of the February Revolution of 1917 (the first phase of the Russian Revolution of 1917), Stalin was released from exile. On March 25 he returned to Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) and, together with Lev Kamenev and Matvei Muranov, ousted Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov as editors of Pravda, the official Bolshevik newspaper, while Lenin and much of the Bolshevik leadership were still in exile. Stalin and the new editorial board took a position in favor of supporting Alexander Kerensky's provisional government (Molotov and Shlyapnikov had wanted to overthrow it) and went to the extent of declining to publish Lenin's articles arguing for the provisional government to be overthrown. However, after Lenin prevailed at the April Party conference, Stalin and the rest of the Pravda staff came on board with Lenin's view and called for overthrowing the provisional government. At this April 1917 Party conference, Stalin was elected to the Bolshevik Central Committee with the third highest total votes in the party.

In mid-July, armed mobs led by Bolshevik militants took to the streets of Petrograd, killing army officers and bourgeois civilians. They demanded the overthrow of the government, but neither the Bolshevik leadership nor the Petrograd Soviet were willing to take power, having been totally surprised by this unplanned revolt. After the disappointed mobs dispersed, Kerensky's government struck back at the Bolsheviks. Loyalist troops raided Pravda and surrounded the Bolshevik headquarters. Stalin helped Lenin evade capture and, to avoid a bloodbath, ordered the besieged Bolsheviks to surrender.[10]

Convinced Lenin would be killed if caught, Stalin smuggled Lenin to Finland. In Lenin's absence, Stalin assumed leadership of the Bolsheviks. At the Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik party, held secretly in Petrograd, Stalin was chosen to be the chief editor of the Party press and a member of the Constituent Assembly, and was re-elected to the Central Committee.[10]

In September 1917, Kerensky suspected his newly-appointed Commander-in-Chief, General Lavr Kornilov, of planning a coup and dismissed him. Believing Kerensky was being controlled by the Bolsheviks, Kornilov decided to march his army on Petrograd. In desperation, Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help and released the Bolsheviks, who together raised a small army to defend the capital. In the end, Kerensky convinced Kornilov's army to stand down and disband without violence. However, the Bolsheviks were now free, rearmed and swelling with new recruits and under Stalin's firm control, whilst Kerensky had few troops loyal to him in the capital. Lenin decided the time for a coup had arrived. Kamenev and Zinoniev proposed a coalition with the Mensheviks, but Stalin and Trotsky backed Lenin's wish for an exclusively Bolshevik government. Lenin returned to Petrograd in October. On October 29, the Central Committee voted 10-2 in favor of an insurrection; Kamenev and Zinoniev voted in opposition.